WHAT is Black Power?

The term is subject to differing interpretations. In 1970, Brinsley Samaroo, an Indo-Trinidadian and participant in Black Power, viewed it “… as part of a worldwide struggle for awareness among black people, seeks to revive our folklore which the British banned as primitive, our art and our customs brought by our forefathers…. It is seeking to make the black man aware of himself and of his capacities and thus enable him to take his future in his own hands and not trust it to people who still doubt that any black man has talent.”

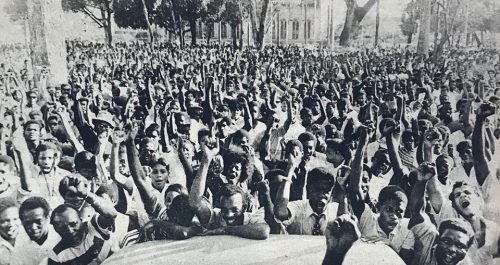

During the late 1960s and 1970s, Black Power appealed to a wide cross-section of the public, including academics, trade unionists, and the underprivileged. In Trinidad and Tobago, the Black Power movement highlighted the economic problems, racism, and social crisis facing T&T. This included removal of restrictions from certain jobs and reduction of the racial tension between Afro-Trinidadians and Indo-Trinidadians.

This year is the 52nd anniversary of the Black Power Revolution in Trinidad and Tobago. The presence of Indo-Trinidadians (East Indians) in the Black Power movement has generated considerable debate.

Members of the public would be familiar with names as Chan Maharaj and Winston Leonard. Dr Ken Parmasad, a former lecturer in the History Department at St Augustine, and one of the Indians involved in the 1970 movement acknowledged the perception that whilst the demonstrations and platform speeches reflected a desire for unity between East Indians and Africans, “the cultural symbols which dominated the movement were Black/African.”

In 1970, Prof Samaroo noted that the majority of Indians did not want to be identified as “Black”. He also stated that the Indo-Trinidadian did not feel welcome in the Black Power movement because wearing of the dashiki was associated with Africa and the symbol of the clenched fist was taken from the Black Panthers, an Afro-American group, in the United States.

Shiva Naipaul, brother of V S Naipaul, in an interview in March 1970, contended that the role of the Indian within the Black Power movement was “vaguely defined”.

Professor John La Guerre contended that the Society for the Propagation of Indian Culture (SPIC) was formed in 1969 as a reaction to NJAC and their promotion of African culture. Prof La Guerre contended that the main objective of SPIC “…was to warn the ideologues of Black Power that their views of the Indian community should not be based on the small class of educated elites. The foreign educated Indian intelligentsia, they argued, were marginal to the villages.”

There were myths in 1970 which contributed to the fears among both major races. Dr Walton Look Lai noted that two of the myths are the Indo-Caribbean is financially better off than the Afro-Caribbean and secondly, that the Indo-Caribbean needed to abandon their culture and heritage if there was any possibility of racial unity and solidarity.

On March 12, 1970, the much anticipated “Caroni March” materialised, which covered 33 miles from Port of Spain in North Trinidad to Couva in central Trinidad. These were token signs of unity, which is obvious, as fewer than 100 East Indians were present in an estimated crowd of 5,000 to 10,000.

During the first leg of the journey, the marchers passed in front of the home of Bhadase Sagan Maharaj, an Indo-Trinidadian in Champs Fleurs in North Trinidad, where he was seated in his garden with a rifle surrounded by security guards.

Bhadase was the president general of the All Trinidad Sugar and General Workers Union and this march threatened his political and ethnic bases. Maharaj was also prominent in the Hindu community. At Curepe Junction in North Trinidad, some university students joined the marchers.

The final phase occurred along the Southern Main Road toward Caroni. A pledge was taken by the marchers “not to harm our Indian brothers but to take positive action against all who we deem responsible.” Ken Parmasad, an Indo-Trinidadian, was one of young members of the Society for the Propagation of Indian Culture (SPIC), who supported Black Power identified the pivotal role of SPIC in ensuring the Caroni March was successful.

The emergence of Black Power during the 1960s signified a struggle to reclaim authority, power, identity and respect. Black Power in the United States was a response to many years of racism faced by African Americans and that turbulent era was marked by discontent with the “establishment” and rejection of conventional politics.

Dr Jereome Teelucksingh is

![]()