THE early Spanish intruders in the late 15th Century and the other Europeans who followed viewed the religious world as two dimensional.

Persons were seen as being Christian or non-Christian. This has not disappeared and in the 21st Century, the non-Christians are sometimes accused, by some Christians, as being heathens and pagans.

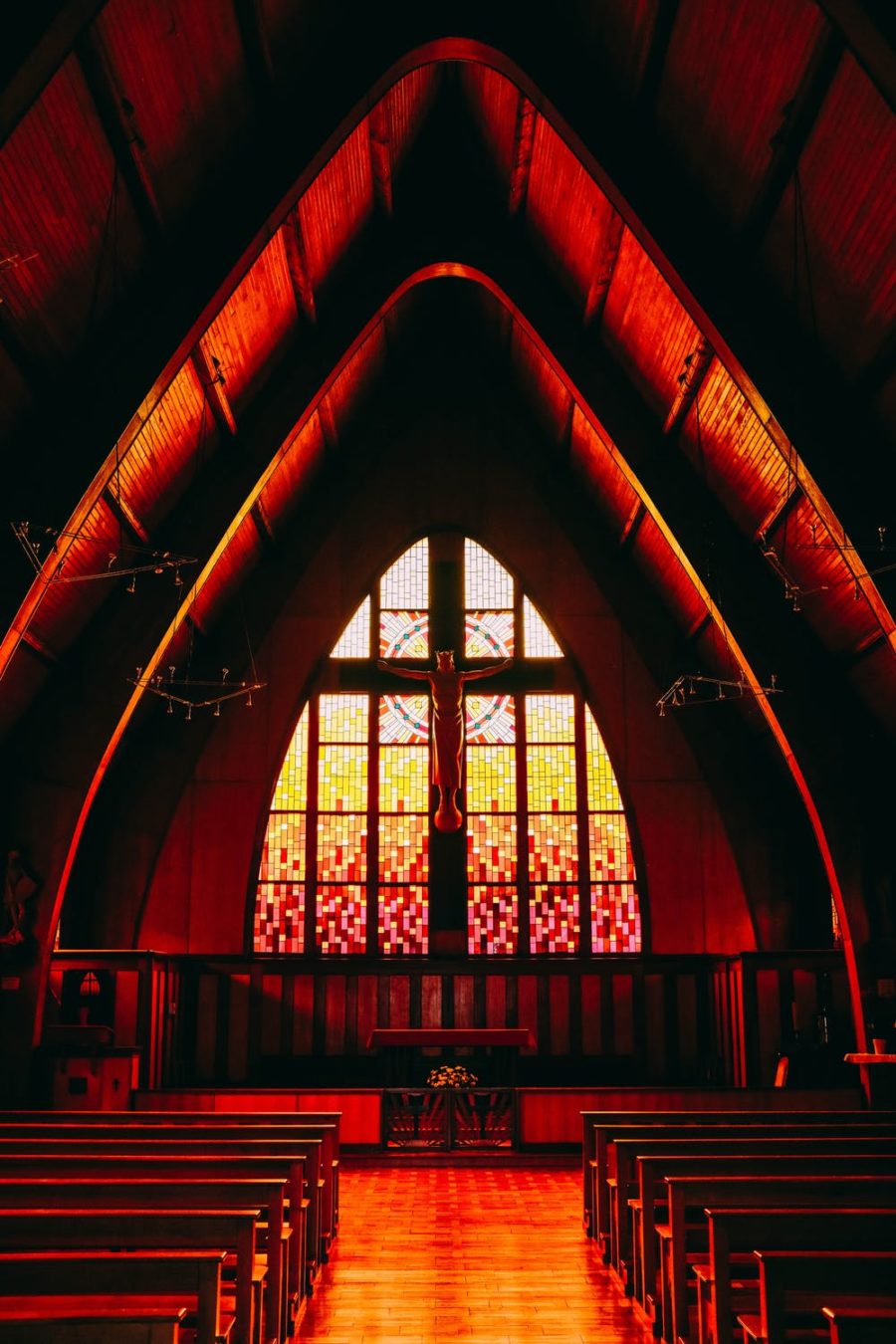

Religion in the Caribbean has a diverse social and cultural history. The sociological processes of adaptation, syncretism and assimilation which occurred among Caribbean religions have made us one of the most unique regions in the Western Hemisphere.

Religion has proven to be a very contentious issue. It would be easier to discover a snowflake on our beaches than to achieve consensus among the various religions and denominations. Sometimes there is subtle friction among the many denominations and sects partly due to doctrinal differences.

The underlying proselytizing goals of some religious institutions, particularly those with fundamentalist beliefs, have intensified the religious tension in the region. The differences among the many sects and denominations have been entrenched in our Caribbean psyche. Most religions exhibit a group consciousness, are wary of their public image and numerical strength in relation to other religions.

How could we expect to achieve a semblance of Caribbean unity in such a volatile environment when mutual respect of other religions and denominations is glaringly absent? There is a dire need for reconciliation among religious leaders to resolve tensions, remove fears, and establish a degree of tolerance and understanding of all religions.

The majority of our Caribbean religions have been transplanted from abroad.

Influences from Europe, Canada, India, Africa and the United States have contributed to the religious diversity. Many of the Afro-Caribbean religions and institutions in the Caribbean have undergone syncretism.

There are such religious expressions as Rastafarianism and the Kumina cult in Jamaica. Similarly, Baptists, Voodoo (vodoun) in Haiti and Candomble in Brazil and the Orisha in Trinidad have retained African customs and practices. These religions should command the same respect as traditional, mainstream Christian faiths.

The Haitian houngan or cult priest who performs rituals relating to the Yoruba, Dahomey, Ibo and Dahomey religions should be recognized and respected as any Catholic priest, pastor, pundit or imam. Likewise, the shrines of the Djuka bush people of Suriname and the tribes of Latin America must be seen as belonging to the family of Caribbean religions. The existence of the Caribbean conference of Churches is tangible evidence that regional efforts are being made to promote Christian unity. And other demonstrations and religions should consider a similar action to promote Caribbean integration through religion.

Followers and worshippers need to appreciate the fact that all denominations and religions underwent sociological and historical transformations in their adaptation to a new environment. Citizens need to intervene to create a tolerant atmosphere. Unless this framework of understanding is constructed then the regular theme of “unity in diversity” at conferences and workshops will be a cliché and remain a theoretical construct.

The entire Caribbean must realise the importance of tolerance. Doctrines, beliefs, predictions and revelations associated with a particular faith do not grant the privilege to deride persons of other religions or denominations. Anyone acknowledging the existence of a Supreme Bring or Creator deserves our respect. Likewise, we need to respect and tolerate those persons who do not belong or adhere to any religion but see themselves as spiritual. Only when this is occurring can we expect to create a harmonious environment.

In a multicultural society, such as the Caribbean, there will always be the potential divisiveness of religion. And it is unfortunate that Caribbean unity is often compromised for the sake of religion.

Dr Jereome Teelucksingh is a recipient of the Humming Bird (Gold) Medal for Education and Volunteerism. He is attached to the Department of History at the University of the West Indies at St Augustine. He has published books, chapters and journal articles on the Caribbean diaspora, masculinity, culture, politics, ethnicity and religion. Also, he has produced a documentary – Brown Lives Matter and presented papers at academic conferences.

See other articles by Dr Jerome Teelucksingh:

Caribbean Youth Need Optimism, Patriotism

Rethinking Identities in Caribbean, Latin America

November 19: All Inclusive International Men’s Day

Should International Agencies be Blamed for Unemployment

A Need to Observe Word Unemployment Day

An Ideology for the Trade Union Movement

The Man who Couldn’t be Prime Minister

Social Outburst vs Social Revolution

Challenges of the Men’s Movement

If George Floyd was Denied Parole

The Meaning of Indian Arrival Day in T&T

International Men’s Day – A Way of Life

Wounds that cause school violence

May Day: A Time for Solidarity, Strength

Who Coined the Term ‘Black Power’

![]()