‘According to Minister of Finance Colm Imbert, a five per cent increase over the period could result in a backpay payment of over $9 billion and a permanent recurrent expenditure increase of over $2 billion’

ONCE again, the delicate process of wage negotiations are underway with the unions dutifully seeking to get just dues for their members.

For the eight-year period between 2015 to 2021, unions are hopeful for increases ranging from 15 per cent to as high as 25 per cent, according to media reports.

Understandably, in this context, union leaders expressed bitter disappointment, anger and rebuke of the two per cent offer that came from the CPO. The unions’ argument or rising cost of living over the period is a valid one. Indeed, inflation has persisted, albeit at lower rates, over the period of time.

However, another end of this argument has emerged as presented by the minister of finance. This relates to the ability of the government, given the country’s delicate financial position, to finance large or even minimal wage increases.

While many of us, myself included, may tend to view the issue of wage increases from a personal perspective, the managers of our resources must take a more responsible approach. Indeed, it will be good politics to grant wage increases to the almost 100,000 workers clamouring for the rise at this time but what will be the impact on the government’s purse?

To easily grasp a fundamental principle of wage increases from the government’s perspective, we have to understand the impact is initially twofold. Firstly, there are arrears, or the back pay, which will have to be paid. These are one-time payments but tend to be very significant. Secondly, there is the more permanent impact on the government’s recurrent wage bill, which will rise by the magnitude of the increase, every year thereafter.

So, in granting any wage increase or, in deciding the parameters for wage negotiations, a government must first estimate the impact of such increases on its finances.

Questions have to be asked regarding the one-time impact of the backpay as well as the permanent impact on the recurrent wage bill. A government must then decide if this increase can be sustained and most importantly, determine where this excess money will come from.

To put this into perspective, the minister of finance recently provided some of these figures to the nation. According to the minister, the annual public sector wage bill is $19 billion, amounting to 40 per cent of our annual revenue. Of course, this is just part of the cost of keeping the public service and state sector running. But what will be the impact of this already large salary bill if the requested increases are granted?

According to Minister of Finance Colm Imbert, a five per cent increase over the period could result in a backpay payment of over $9 billion and a permanent recurrent expenditure increase of over $2 billion.

Given the already tight budget conditions under which the minister of finance has to operate under, one has to wonder, how will this be funded?

In the recent mid-year review, it was indicated that this country had benefitted from increased revenues due to elevated energy prices, however, this has come after over a decade of running deficits, in other words, borrowing. It will be highly imprudent to commit the minimal increase in revenue that is being seen now, towards large permanent recurrent expenditure increases and a massive one-time payment. Instead of taking advantage of our good fortune, this may in fact dig us deeper into an economic hole.

We only have to look to 2014, when wage negotiations were taking place. Energy prices began to collapse and continued their spiral, severely affecting government revenues. However, the government of the day saw it fit to grant a five per cent wage increase in an election year. The new PNM administration, upon coming into office, was encumbered with this obligation to pay over $5 billion in arrears and a significant permanent increase in recurrent expenditure, at a time when almost $16 billion in energy revenues was lost due to low prices. In this scenario, the government borrowed this money to cover its obligation. This is a highly impractical and imprudent approach towards managing the issue of wage increases and is unsustainable.

A logical and more pragmatic approach is needed where the conversation should focus on what can be afforded as well as providing just dues to workers. I have not heard the conversation on productivity and efficiency, which is an essential element of any enhanced compensation package.

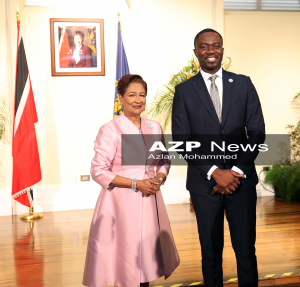

Vyash Nandlal hold a Bachelor’s degree in Economics and an MSc in International Finance. He has more than 12 years’ experience in the field of economic research and analysis. He currently works as an economic researcher and advisor in the Office of the Prime Minister and sits on the boards of several state and non-profit organisations. The opinions and comments expressed by him are not necessarily those of AZP News, a Division of Complete Image Limited.

![]()