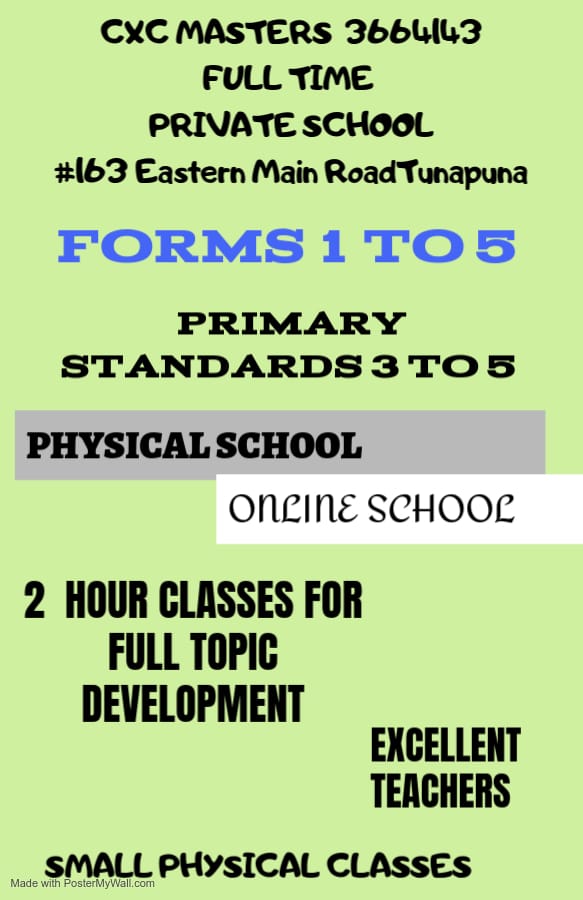

Caption: A man carries one of the three Sakalava skulls during a ceremony for their restitution to Madagascar, at the Culture Ministry in Paris, on August 26, 2025.

PARIS – France on Tuesday returned three colonial-era skulls to Madagascar, including one believed to be that of a Malagasy king decapitated by French troops during a 19th-century massacre.

The skull, believed to belong to King Toera, was handed over in the first restitution of human remains since France passed a law facilitating their return in 2023, along with those of two other members of the Sakalava ethnic group.

French troops beheaded King Toera in 1897, with his skull then taken as a trophy to France.

It was placed in Paris’s national history museum alongside hundreds of other remains from the Indian Ocean island.

“These skulls entered the national collections in circumstances that clearly violated human dignity and in a context of colonial violence,” said French Culture Minister Rachida Dati.

Her Madagascar counterpart, Volamiranty Donna Mara, praised the handover as “an immensely significant gesture” that marked “a new era of cooperation” between the two countries.

“Their absence has been, for more than a century, 128 years, an open wound in the heart of our island,” she said.

A joint scientific committee confirmed the skulls were from the Sakalava people but said it could only “presume” that one belonged to King Toera, Dati said.

Since his election in 2017, President Emmanuel Macron has acknowledged some past French abuses in Africa.

On an April visit to the capital Antananarivo, Macron spoke of seeking “forgiveness” for France’s “bloody and tragic” colonisation of Madagascar, which declared independence in 1960 after more than 60 years of colonial rule.

The skulls are set to return to the Indian Ocean island on Sunday, where they will be buried.

‘Bloody, tragic’

In recent years France has sought to reckon with its colonial past, sending back artefacts obtained during its imperial conquests.

But the country was hindered by its legislation, which required a special law be passed for each restitution — as in 2002, when South Africa sought the return of “Hottentot Venus”, a woman displayed in 19th-century Europe as a human curiosity.

To speed up the process, France’s parliament in 2023 adopted a law facilitating the repatriation of human remains.

With a third of the 30,000 specimens at Paris’s Musee de l’Homme made up of skulls and skeletons, countries including Australia and Argentina have filed their own restitution requests for ancestral remains.

France passed a separate law the same year to streamline the return of art looted by Nazis to Jewish owners and heirs.

But a third law enabling the return of property taken during the colonial era has not been finalised.

If approved, the legislation would make it easier for the country to return cultural goods obtained through theft, looting, coercion or violence between 1815 and 1972, according to the culture ministry.

A new version of the bill was presented at a government meeting in late July, with Dati saying she hoped it would be adopted “quickly”. (AFP)

![]()