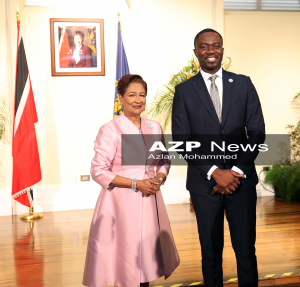

AZP News Guest Commentary

By Prof Rajendra Ramlogan

FOR generations, the children of the South made their way north with nothing but ambition in their book bags and sacrifice in their bones.

Mothers pawned wedding bayras, fathers worked overtime in the fields and factories, and entire families pooled what little they had so one child might find a place at The University of the West Indies, St Augustine. It was a pilgrimage of hope.

Students from areas such as Penal, Siparia, Debe, and Princes Town carried with them not just books, but the burden of geography, knowing that education was their one shot at transcendence. The groups of aspirants even included a lone pilgrim from Robert Hill.

UWI was the promised land, but it lay beyond the reach of many, not because of intellect, but because of distance, cost, and the cultural weight of leaving home. And so, when the idea of a South Campus was first mooted, it was not just welcomed—it was consecrated in memory of those sacrifices, as an overdue act of justice.

It began as a promise—one that shimmered with the possibility of transformation for the long-neglected southern belt of Trinidad. The Debe South Campus of UWI was more than concrete and steel; it was the crystallisation of decades of southern yearning for equitable access to higher education. Announced under the People’s Partnership Government, the vision was unapologetically bold: to decentralise academia and place the heart of scholarship in the very soil where cane once grew and where generations of children dreamt beneath corrugated roofs.

Debe, long seen as peripheral to Port of Spain’s gravitational centre, would now host faculties of law, education, and the creative arts—disciplines that had too often been cordoned off by geography and class. It was to be a university for the South, of the South. A university, finally, that saw us. Debe would no longer be only known for its exquisite and sought-after Indian delicacies.

But from the moment of its conception, the Debe South Campus was shadowed by a vision that did not see it, at least, not how the South saw itself. The People’s National Movement, steeped in a tradition of north-centric governance, had long defined national development through the prism of Port of Spain and its surrounding corridors. In that framework, the South existed as an afterthought, a place of extraction—of labour, oil, and cane—but not of intellect or innovation.

When the PNM returned to power, the fate of the campus shifted almost overnight. Construction slowed, then stalled. Entire buildings stood completed yet empty, silent monuments to a dream deferred. There was no outright closure—only a quiet abandonment, bureaucratically dressed in language about reviews, priorities, and fiscal prudence. But to the people of the South, it was something more intimate and painful: a betrayal. A reaffirmation that, in the eyes of the State, education was a privilege tethered to geography, and some geographies mattered more than others.

And yet, in the midst of this betrayal, the role of UWI must also be scrutinised. The Debe South Campus, built with taxpayer funds and heralded as a cornerstone of southern upliftment, was quietly sidelined. No serious pressure was exerted on the State to operationalise it. No public advocacy for its activation. Forgotten was the driving ethos of education in a developing country—that education must be a tool for redress, not reinforcement, of social and spatial inequality.

Finally, the return of the UNC-led government has led to the announcement that the dream of the South has returned. However, this travesty of justice cannot be allowed to fade into the quiet amnesia of national mismanagement. It demands a proper, independent investigation—not as an act of vengeance, but as a necessary reckoning with the truth.

The people of the South were promised access, inclusion, and dignity through education; what they received instead was neglect wrapped in excuses. The millions spent, the dreams deferred, and the glaring absence of accountability represent a betrayal not only of a critical geographical section of our nation but of the very principle of equitable development.

If state projects can be so casually abandoned without consequence, then what protection do the people have from political whimsy masquerading as policy? There must be answers. There must be transparency. And above all, there must be consequences—not just to restore faith in our institutions, but to ensure that never again will the hopes of a people be built, then left to rot behind.

![]()